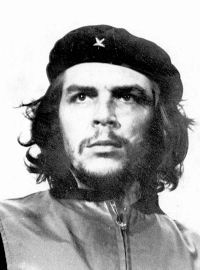

Che Guevara, photo Alberto Korda

Ernesto 'Che' Guevara is perhaps the most recognisable revolutionary icon, his image having graced countless posters and t-shirts.

For some it is just a fashion statement, but many are drawn to him as a symbol of the struggle against capitalism and the fight for a better world.

Films such as the Motorcycle Diaries and the two-part biopic 'Che' reflect his enduring popularity and give a glimpse of how his political ideas developed.

Revolutionaries do not fall ready-made from the sky, but are formed by conditions and events. In 1950 the asthmatic Guevara began his series of travels around Latin America as a 22 year old middle class medical student, seeking only youthful adventure.

But these experiences were to shape the rest of his life. On these journeys he witnessed the enormous class divide that existed between the "luxurious façade" and the real "soul" of the continent, the poor and downtrodden.

Seeing the struggles of workers and the poor everywhere he went, Guevara's attitude evolved from sympathy, through support, to active participation.

It was also on these travels that he was given the nickname Che, due to his Argentinian accent.

26 July Movement

It was in Mexico in 1955 that Che first met Fidel Castro and joined his 26 July movement. At the time Cuba was under the dictatorship of Fulgencio Batista, who had come to power through a military coup.

Its economy was completely dominated by US big business and wealthy Americans frequented the many Havana brothels and casinos.

Castro wanted a modern capitalist state in Cuba with some reforms for the poor. He envisaged a guerrilla struggle to overthrow only the dictatorship, not capitalism.

Even after returning to Cuba he told a journalist: "we have no animosity towards the United States... we are fighting for a democratic Cuba and an end to dictatorship".

Che himself was, by this point, an avowed socialist but joined the movement as a way to get active in the struggle.

He had previously criticised the Stalinist 'popular front' policy, promoted by the Cuban Communist Party.

This was the idea that in Latin American countries the working class was not ready to take power and establish a socialist society and instead had to make alliances with the 'progressive' sections of the national capitalist class in order to defeat imperialism.

He had seen first-hand how these so-called progressive capitalists were prepared to use bloody repression against the workers to defend their own interests.

However, while correctly criticising this approach, Che did not propose an alternative. He had not absorbed the lessons of the Russian Revolution nor the writings of its leaders, Vladimir Lenin and Leon Trotsky, particularly on the role of the revolutionary party and Trotsky's theory of the permanent revolution.

Trotsky's theory

Trotsky explained that the capitalist class in countries with developing capitalist economies such as Cuba was dominated by imperialism and unable to play the independent role that it had in the capitalist revolutions such as in Britain.

It was therefore incapable of carrying out its historical role and the tasks of land reform, establishing capitalist democracy and creating an independent nation state.

Trotsky argued that these steps could only be achieved through socialist revolution: nationalising industry, taking its ownership and control out of the hands of the capitalists and establishing a planned economy under democratic workers' control.

Trotsky said that the working class, even when in a minority, must lead the struggle against capitalism.

The decisive role of the working class arises from its role in production and the collective consciousness which develops in the workplace and lays the basis for the collective democratic control and management of society.

Because of isolation in rural areas and an individualistic outlook, the peasantry cannot lead such a transformation, but can still play in important role in the struggle.

This theory was borne out in the course of the 1917 Russian Revolution when the working class, in the period immediately after 1917, established the most democratic state in history.

But Che was not an active member of any organisation that understood the lessons of 1917. He instead saw the peasantry as the most revolutionary class and the methods of guerrilla struggle as the most effective.

He was influenced by many factors, including his own class background, the abandonment of an independent working class approach by communist parties and the victory of Mao's peasant army in the Chinese revolution.

Cuban revolution

It was December 1956 when a small band of fighters, Che and Castro among them, landed in Cuba. The landing was plagued with errors and accidents and two days later, when the scattered guerrillas managed to regroup, they were reduced in number from 82 to just 20. But just over two years later they had forced Batista to flee the island.

Che thought the guerrilla struggle would ignite a revolutionary movement, especially among the peasantry.

But while the guerrillas drew support, the mass of the population - especially the urban working class - were not active participants in the struggle.

Che gained a reputation as a courageous fighter and leader. He also organised political discussions among those under him and argued for socialist ideas within the 26 July Movement.

The guerrilla forces grew as they were seen as the only force consistently opposing the Batista dictatorship.

In marked contrast to the brutal treatment they received at the hands of the regime, the guerrillas did not execute the soldiers they captured.

Instead they discussed politics with them and let them go, winning an increasing number of defectors from the army.

On 1 January 1959, with his regime crumbling and the guerrillas approaching the cities, Batista fled the country.

The only successful general strike since Che's arrival on the island was called for the following day, which greeted the guerrillas as they marched into the major cities.

Despite Che arguing for it, Castro's intention had never been the overthrow of capitalism. It was over a year later when he first described the revolution in Cuba as 'socialist'.

He was pushed to take measures of nationalisation by the pressure of the masses combined with the reaction of American imperialism.

As the US recoiled, Cuba developed greater trade and political links with the Soviet Union. The 26 July movement merged with the Communist Party and became the organ of one party rule.

Capitalism overthrown

The Cuban revolution broadly bears out the theory of the permanent revolution. Castro's vision of an independent, democratic, capitalist Cuba was impossible; the Cuban revolution overthrew capitalism.

But workers did not play an active role in the revolution, so their role in the subsequent running of society was also passive.

From the outset the planned economy in Cuba was controlled not by workers' democracy, but by a bureaucratic elite, reflecting Stalinism in the USSR.

Despite this, the revolution still brought huge improvements to the lives of ordinary Cubans. Illiteracy was eradicated in just two years and by the late 1970s life expectancy was 74, comparable to Britain and much higher than other Latin American countries, Bolivia's was just 45.

Showing the same spirit of self-sacrifice that had marked him out as a fighter, Che rejected completely the privileges of the bureaucracy.

For this he must be saluted and it is one of the reasons he's still so admired today. Despite his growing disillusionment and revulsion at the bureaucracy, unlike Leon Trotsky he did not propose nor fight consistently for an alternative.

Instead he left Cuba in order to try and spread revolution abroad. This devotion to internationalism was another of Che's best characteristics.

The methods of guerrilla struggle, which succeeded in the specific conditions of Cuba, did not have the same effect elsewhere.

In 1965, Che left for the Congo but his efforts were unsuccessful and he had to make a clandestine return to Cuba.

In 1967 he appeared with a band of guerrillas in Bolivia. Sadly the failure to ignite revolution and resulting defeat of that struggle were to prove fatal to Che.

Che was captured and executed by the Bolivian army, backed by the CIA, at the age of just 39. Throughout his life, the injustices that Che saw motivated him to continue struggling for a better world.

At the same time, the development of his political ideas never stopped. Works by Trotsky were found on him when he was captured.

Che Guevara's position as an icon of struggle is completely justified. But we would not be doing his life justice if we did not examine it 'warts and all'.

His life is an inspiration for all those seeking to fight oppression and change society.

No comments:

Post a Comment